Why I’m Not “Going For It”*

*Full-Time† †Yet

This ad-free and plain ol’ free publication runs on the positive vibes coming from readers like you. Subscribe to send me positive vibes.

“The arts are not a way to make a living. They are a very human way of making life more bearable. Practicing an art, no matter how well or badly, is a way to make your soul grow, for heaven's sake.”

“So are you going for it?”

That’s what friends would sometimes ask me, when I took a “mini-retirement” last year and dove into writing and illustrating Phased and learning about indie authoring by doing.

By “going for it” they meant making a full-time pursuit of becoming someone who can make a living as a [insert creative profession here, comics creator/author in my case].

That’s the dream!

But my response was and is, “Nah—if I were rich, I’d totally do it. But I’m not rich, so here’s why I’m keeping the day job...”

So—er, here’s why I’m keeping the day job:

1. The chances for any individual making it big as an author is comparable to becoming a billionaire.

2. America’s health insurance situation is unaffordable for us not-rich folks.

3. For me, creative freedom is most important.

There’s some more meat on these bullet point bones, so let’s dig in to each of them.

The chances for any individual making it big as an author are comparable to becoming a billionaire.

To begin with, we should set the stage for how much luck is involved, just how unlikely it is for any individual to have massive mainstream success. Then, with clear eyes about our likelihood of success, pragmatic decisions become easily understandable.

Eric Hoel wrote this article last May breaking down how rare it is for someone to be able to make a living as a book author. In essence, he determined how many “self-made” billionaires there were in the US. And then he determined how many non-celebrity authors were “making a living” with their writing.

Self-made billionaires: ~515

Non-celebrity authors making a living: ~585

So…do you feel lucky?

Maybe one could quibble with the details of Hoel’s definitions and calculations, but as he notes, the point isn’t the specific digits of the results—the point is the orders of magnitude are similar. Fiddle with the methodology and you won’t come out to a markedly different conclusion: it’s damn hard to make it as a writer.1

And that’s just “making a living”—not even making it big. Hoel’s definition of “making a living” is exceedingly generous: getting a $250,000 book deal every five years. That’s $50,000 per year averaged out. I’d call $50,000/year in a major city in America just scraping by these days, not “making a living”.

The first section of this article in The Stranger last June painted a picture of how hard it is for artists to live in Seattle by piecing together several pieces of evidence:

A survey of artists carried out by The Seattle Times found that 62% made less than $50,000 in income, and 80% made less than $75,000.

The MIT Living Wage Calculator said that the living wage for a single adult (not a family) living in the Seattle area was $59,696. Combined with point #1 above, this means that a significant majority of artists earn less than a living wage for a single adult.

A Consumer Affairs analysis of Zillow rent data estimated that a single adult needed $87,000 per year to live comfortably.

So if $50,000 per year is an author who’s doing “cultural billionaire” well, what about the non-rockstar (bookstar?) average Janes and Joes of the writing world?

A survey by the Alliance of Independent Authors “found that the average income for self-published authors rose 53% [in 2022] over 2021, reaching a median of $12,749, a figure higher than those of authors at traditional publishers.”

$13,000 is less than the federal minimum wage over the course of a year (assuming a 40-hour work week, $7.25*2080 = $15,080). And the self-published authors were earning more on average than authors at traditional publishers.

Suffice it to say, most authors must have something or someone else they’re relying on to help pay the bills, whether that’s another primary source of income, a partner’s income, or savings. And there isn’t necessarily something wrong with that! We’ll come back to this point.

But on the question of whether or not to quit the day job so you can devote more time to pursuing your creative path, what this analysis tells us is that it’s not simply a matter of work really hard and you’re going to make it. If that were true, we’d have a lot more billionaires and a lot more writers living off their craft alone. I definitely feel the time and energy constraints that having a day job takes away from my creative endeavors, though.

America’s health insurance situation is unaffordable for us not-rich folks.

It’s very well established that our health insurance system in America is expensive compared to other developed nations. Part of why this is the case—our lack of universal healthcare—also means that if you don’t have employer-sponsored health insurance, you need to pay for that expensive care yourself.

This is a big incentive to hold on to a job that provides health insurance until you feel more sure that your boat’s going to float. This situation—our weak social safety net—also makes it more difficult for people to pursue their passions, whether that’s starting a new business or becoming a full-time independent author/illustrator/filmmaker/tapestry weaver/chainsaw ice sculptor/etc. (To be clear, becoming an independent creative can also involve starting a new business if you’re making money by it.)

For me, creative freedom is most important.

Ok, but achieving massive mainstream success is different from being a working creative professional, and aren’t there people who write and/or illustrate for hire as their day job?

This third point is a key point in why I’m not “going for it”. Yes, there are certainly paths to making a living using writing and illustrating skills working for hire or for others. But in this case you’re helping to produce other people’s (or corporations’) vision. This means you aren’t paying your bills only with your personal art.

Consider this video by Luc Forsyth, explaining why filmmakers are all broke.

Forsyth notes that he actually earns enough to live a middle class2 lifestyle in an expensive city like Toronto, but it’s by working for hire and not as an “auteur”. Forsyth distinguishes between a “filmmaker”, which he’s not, and a “film-worker”, which he is. Although filmmakers take on the difficult task of raising funds and doing whatever it takes to turn their vision into a reality, and end up burning their own resources to get their projects over the finish line, the creative professionals who they hire to help realize their dreams are (or can be) paid decently.

Forsyth goes on to point out that Leonardo DaVinci worked a day job (or “paycheck job”, a great term I recently learned from my college art professor advisor) to fund his studio, too (for example, designing war machines for a rich client…oof). I had similarly thought back to the Gothic and Renaissance eras, where much of the European art we can see today from those times were religious works, sponsored by religious institutions, and portraits of wealthy benefactors. To my statement earlier about how there isn’t necessarily something wrong with relying on another source of income or savings to support one’s artistic practice, it’s just long been difficult to live off of one’s auteur art alone.

Now, you don’t have to take every job that comes your way, regardless of how distasteful you might find it. And creatives who’ve built up enough of a reputation that they can be selective about the jobs they take on may be able to maintain a pipeline of projects that they find fulfilling to be a part of.

Still, there’s a difference between bringing to life ideas that are uniquely you versus helping to bring someone else’s vision into the world. Reflecting the creator’s unique perspective is at the core of all the best artwork. Ryan Coogler talked about making something “uniquely personal” driving his creative decisions behind his blockbuster original movie Sinners. The question “What’s a story that only I can make? That—without me—this story will never be made?” guided Jon Chu in making the smash hit movie adaptation of Crazy Rich Asians.

This is not to diminish the work of the creative professionals working for hire. We need all types—big projects, like movies and feature length animated films, TV shows, theater productions, video games, or even some larger comics and graphic novel projects require multiple people to produce. In the case of big animated movies and video games, sometimes hundreds of creatives several years to produce. And absolutely no shade on people for whom working a creative day job is the right path.

But for me at least, I want to be able to bring to life the things that are intriguing to me. Working as someone else’s (or a company’s) appendage is not appealing to me.3 There’s something to be said, too, for how if I relied on comics to pay the bills and worked at it all day every day, I’d want to do something else in my leisure time. I was a very liberal arts kid through high school and college.

To be a full-time creative, which for me would mean necessarily working for hire (because I don’t think I have a mind for wide mainstream commercial appeal), seems like it might actually be less fulfilling to me than working a day job that I feel like does something good for society and uses my other skills, while pursuing my creative visions with the rest of my time.4

So there you have it. It’s so rare to make it big as an author that you have to go into it loving the doing of the art, itself. I happen to have developed a lot of other marketable skills that allow me to find steady work with good pay and benefits. And creative freedom to bring my own ideas into the world is so important to me that the independence that a solid day job (that still affords enough time and energy outside of it) provides for my art is actually a considerable plus. Putting those together leads me to follow my current path of not “going for it”—not full-time at least—yet.

But if for some reason lots of people were to like my work and it blew up big, hell yeah I’d ride that wave!

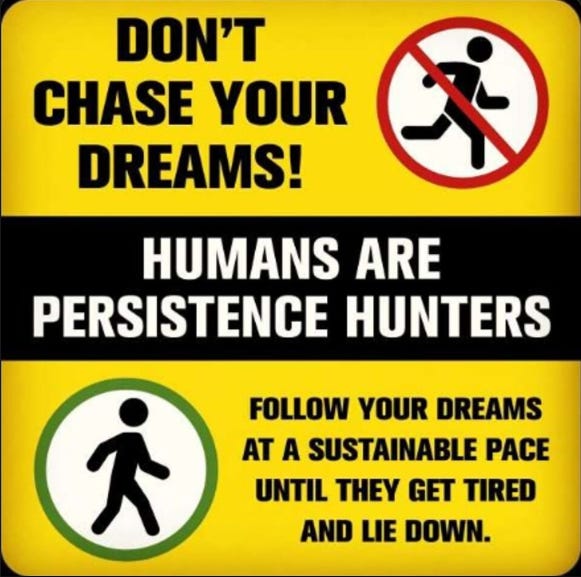

I don’t know who originated this meme, as it resurfaces in the ether from time to time, but this is basically my approach:

But I’d add that for me, the sustainable pursuit is also, itself, the dream.

Bringing it back to Vonnegut, quoted at the top of this essay, I think he’s got a good way to think about it. You practice the arts at base because it’s something you find fulfilling, and not because you think you’ll make a good living doing it. Ideally we’d have a social and economic system where the arts could sustain you both spiritually and financially. But until then, despite the difficulties, despite there being no promise of popularity or profit, despite the fact that powerful people take advantage of creatives to enrich themselves, artists will keep creating regardless. Because it makes life more bearable. Because it makes your soul grow.

Hoel walks through his methodology in detail in his article, and you can decide for yourself if it seems reasonable.

But everyone thinks they’re middle class, even people making large six figure salaries in New York and San Francisco.

Though, I can see there being some stories of other’s that I’d be excited to help tell. And depending on the project and your collaborators, you may have more or less artistic voice in the part you’re playing.

I’d ideally like a different balance between the amount of time on the day job and the creative work, though…

Agree with all of this, though it took me so many years to get there. I think this is the most responsible advice you can give to a young creative person.

It’s too late for that person to be me but I can join this chorus and of course, keep making things!

Definitely a subject I’ve reflected on frequently, or as they say on the internets, “relatable content!”