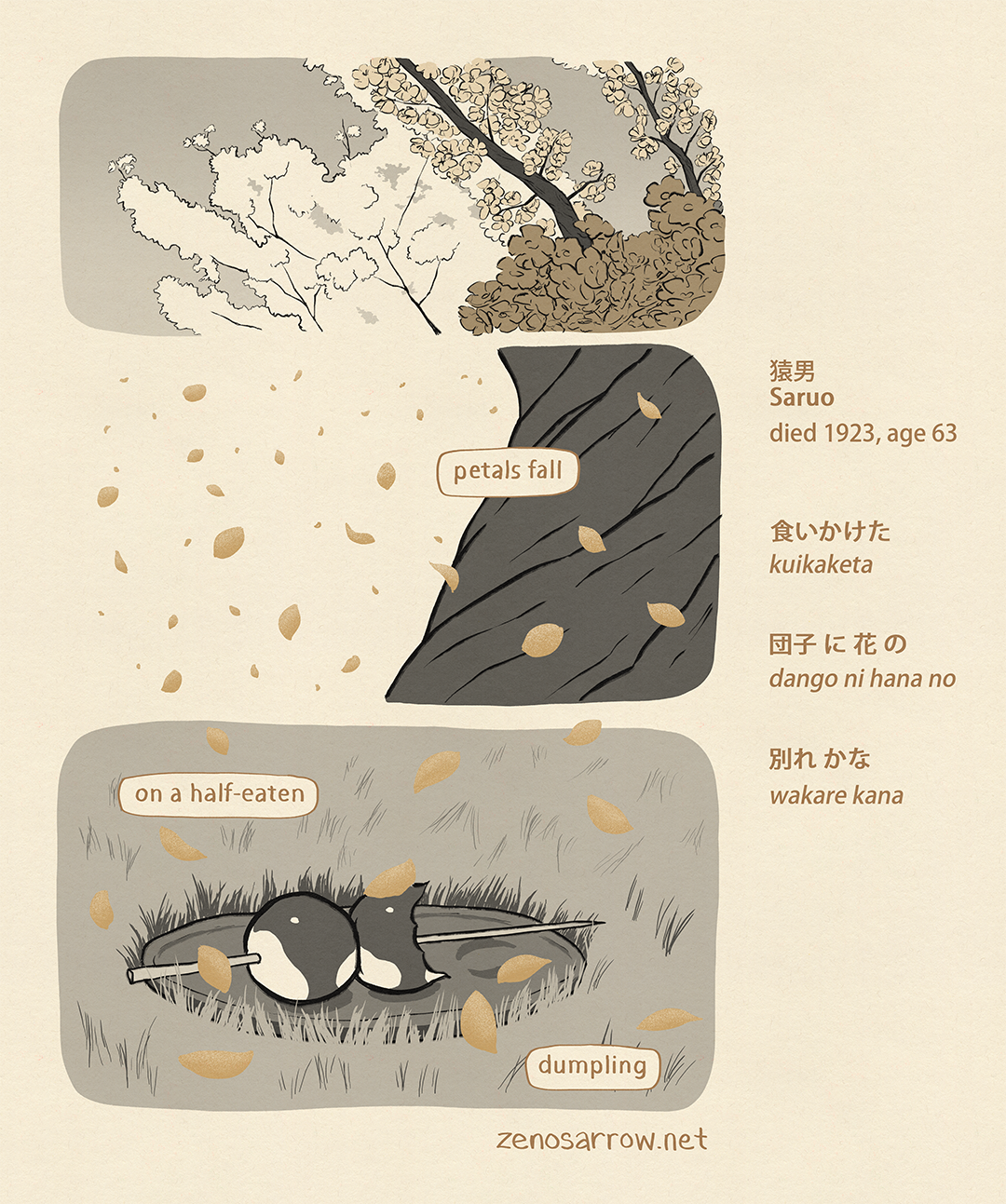

Saruo's Dumped Dumpling

An early modern Japanese death poem by Saruo, translated and illustrated as a poetry comic

A couple quick event announcements before we get to the comic:

Mark your calendars, everybody! Come see me at Hot Off the Press Book Fair on 7/12 and Seattle Zine Fest on 7/20.

I know I know, I mentioned them before, but now I know they’re really happening. I’ll follow up when I know my table details. Get stoked!

Ok, on to the comic.

This is the fourth in a series I’m doing of haiku comics around the death poems (jisei), farewell notes to life, of early modern Japanese poets. Learn more about this project, Japanese cultural context, and haiku, and find links to the other comics in this series here: death haiku comics.

This ad-free and plain ol’ free publication runs on the positive vibes coming from readers like you. Subscribe to send me more positive vibes.

猿男の辞世 Saruo’s Death Poem

猿男 Saruo (died 1923, age 63)

食いかけた

kuikaketa

団子 に 花 の

dango ni hana no

別れ かな

wakare kana

Translation:

petals fall

on a half-eaten

dumpling

Notes

Saruo does something really cool with his poem: by evoking something half-eaten, he implies the presence of a person by their absence—like using negative space but for verbal description instead of for visuals. Why didn’t they finish eating the dango? Where did they go? In the context of a death poem, with the petals falling on the unfinished snack, this is poignant.

On dango:

Dango are rice dumplings, often grilled and glazed. As Hoffmann notes, one common occasion for eating dango is while enjoying the cherry blossoms (an activity called hanami, or flower viewing) in spring.

On flowers:

Buddhism came to Japan via China in the seventh century, and over the following centuries came to have more and more influence on Japanese culture. This included the view that life is an illusion or dream.1 During the Heian period (794-1185) of Japanese history, flowers became the principle symbol representing the ephemerality of life.2

Flowers also appear in Gozan’s poem, and in my comic of Onitsura’s poem.

Fun times with the translation:

This poem was an interesting one for creative decisions interplaying between the verbal translation and my creative choices for my comic interpretation.

I liked the choices Hoffmann made in his translation for several reasons, although I still ended up changing it a little, which I’ll get into.

Although with the other poems I’ve done so far, I felt that Hoffmann’s translation changed things more substantially, with Saruo’s, Hoffmann had a very simple translation. He cut out Saruo’s very poetic turn of phrase, “hana no wakare” (flower’s farewell), and kept it simply that the flowers were falling. I considered bringing back Saruo’s beautiful approach, but to me, the very direct depiction works well with the absence of the person who half-ate the dango.

I also considered changing the ordering back to be like Saruo’s original, where he begins with the dango before mentioning the falling petals. But for the sake of the comic that I was envisioning, the visual flow from top to bottom—looking up at the cherry trees, seeing the petals falling, following them down, and finally landing on the half-eaten dango—meant that Hoffmann’s ordering, starting with the flowers worked better for my purposes.

I almost just went with Hoffmann’s translation directly, but for one thing:

Hoffmann’s translation reads “Cherry blossoms fall / on a half-eaten / dumpling”. As discussed previously, I agree with Hoffmann’s approach of not bothering with the exact 5-7-5 cadence of haiku when translating. But here, with “cherry blossoms fall”, we end up with a 5-5-2 structure. An approach that some English haiku writers take is to more generally make the lines short-long-short. This honors to some extent the spirit of Japanese haiku while freeing English speakers from a constraint that wasn’t designed for the rhythms of our language. Hoffmann’s is in effect long-long-short. I decided to channel the short-long-short spirit in making my translation “petals fall / on a half-eaten / dumpling”, for a 3-5-2 structure.3

Yoel Hoffmann. Japanese Death Poems. (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2018), 36-37.

Ibid., 46.

Another stylistic choice is on whether to capitalize the first letter of the lines.

Oh, the explanation of the ordering was really interesting. I don’t know what the original translation’s justification was for making the 団子 a reveal where it wasn’t originally, but visually it makes a lot more sense if you are drawing falling objects.

It’s cool reading the behind-the-scenes on your work. It’s something I used to do but these days, after finally finishing something, I just want to get it out and be done with it …