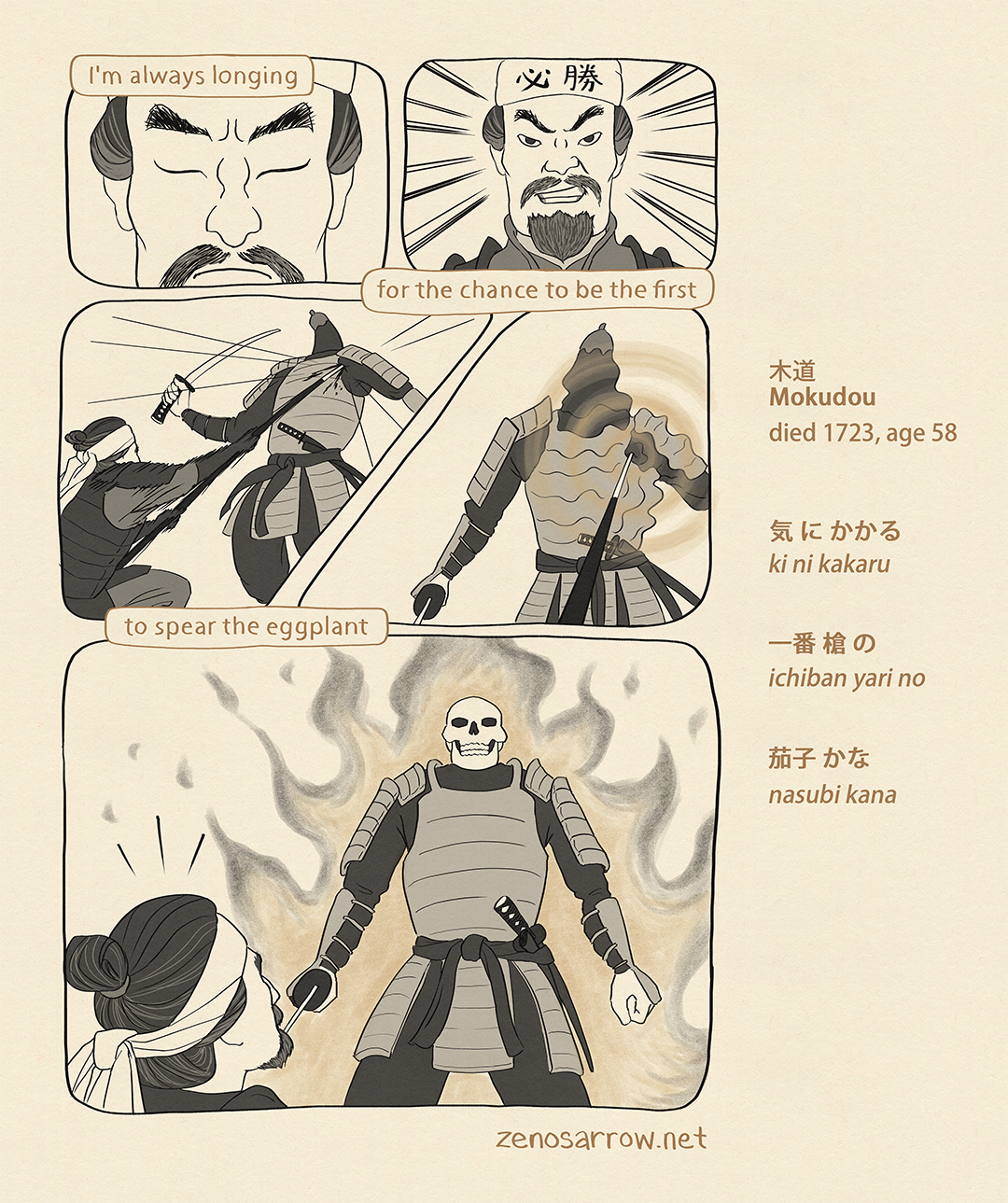

Mokudou's Seeking Samurai

An early modern Japanese death poem by Mokudou, translated and illustrated as a poetry comic

Hey everyone,

One more summer event announcement to put on your calendar! The others were comics/zine fests, but this one is going to be a comics talk/party. The event will be on Sunday 8/3 at 1pm, at Mam’s Books in Seattle’s Chinatown/International District.

Will be nailing down the plan closer to then, but it’ll likely be a casual conversation with another local Asian-American comics creator about our comics and what drew us to making comics, followed by audience Q&A. It’ll be a fun and interesting talk, and you can ask us about our weird indie comics!

Ok, but before then, it’s just two days till Hot Off the Press this Saturday 7/12. See you there.

Speaking of weird indie comics, I have another death haiku comic for you today, below the fold. This one takes a very different tack from the others—to the extent that it kind of misses the point of the assignment? But says a lot about the author in any case.

This is the sixth in a series I’m doing of haiku comics around the death poems (jisei), farewell notes to life, of early modern Japanese poets. Learn more about this project, Japanese cultural context, and haiku, and find links to the other comics in this series here: death haiku comics.

This ad-free and plain ol’ free publication runs on the positive vibes coming from readers like you. Subscribe to send me more positive vibes.

木道の辞世 Mokudou’s Death Poem

木道 Mokudou (died 1723, age 58)

気 に かかる

ki ni kakaru

一番 槍 の

ichiban yari no

茄子 かな

nasubi kana

Translation:

I’m always longing

for the chance to be the first

to spear the eggplant

Notes

On eggplants:

Hoffmann notes that eggplants are a seasonal image for summer, the season in which Mokudou died.1 But beyond indicating the season (which is an important part of proper haiku form), it seems that there isn’t anything connecting the eggplant with some other greater symbolism related to death, or anything for that matter.

In his book, Hoffmann also shares Mokudou’s preface to his jisei, in which he explains:

“In times of war the samurai were the first to stab their [spears]2 into their enemies. We are familiar with many stories about these bold warriors. Today peace reigns in the world and warriors no longer go forth into battle. They continue, however, with military exercises, so that in time of need they will be ready to fight zelously, till word of their courage echoes throughout Japan and the entire world.”

Based on Mokudou’s own preface, it really appears to be the case that the image of stabbing the eggplant is Mokudou’s attempt to shoehorn his samurai fighting spirit into the haiku format.3

And yet, there is something poignant about this samurai, whose life has been dedicated to perfecting his prowess as a warrior, coming to the end of his life feeling like he never got his shot.

Yoel Hoffmann. Japanese Death Poems. (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2018), p. 240.

Hoffmann translates “yari” as “dagger”, but I don’t why. The weapons are clearly long-handled polearms. Maybe there was something lost in translation between Hebrew and English.

Hoffmann used the kinder verb to “blend” his fighting spirit as a samurai with the spirit of haiku.