Hokusai's Great Wave Goodbye

An early modern Japanese death poem by Hokusai Katsushika, translated and illustrated as a poetry comic

Checking in, how’s everyone doing? How’re these death haiku comics landing with folks? I hope you’re finding my visual interpretations both beautiful and fun. I hope the subject matter and my attempts to contextualize it are intriguing. And I hope that altogether these comics and learning about traditional Japanese views on death make it seem less scary and taboo (if it was to you).

This post is the fifth I’ve done in this series, and I think another 3-5 oughtta round out a good set for compilation, depending on what else jumps out to me from the poems in Hoffmann’s book.

Thanks for sticking with me on what struck me as a fascinating and exciting idea for a comics project, and also a totally unique one—for good reason, I guess. ;)

Today’s poet is 北斎葛飾 Hokusai Katsushika—yes, that Hokusai! Creator of the Great Wave that seemingly won’t be returning to the ocean the way Thich Nhat Hanh described we all must,1 as nearly two centuries after Hokusai first made the print, people continue to be taken by its beauty and drama.

This is the fifth in a series I’m doing of haiku comics around the death poems (jisei), farewell notes to life, of early modern Japanese poets. Learn more about this project, Japanese cultural context, and haiku, and find links to the other comics in this series here: death haiku comics.

This ad-free and plain ol’ free publication runs on the positive vibes coming from readers like you. Subscribe to send me more positive vibes.

---

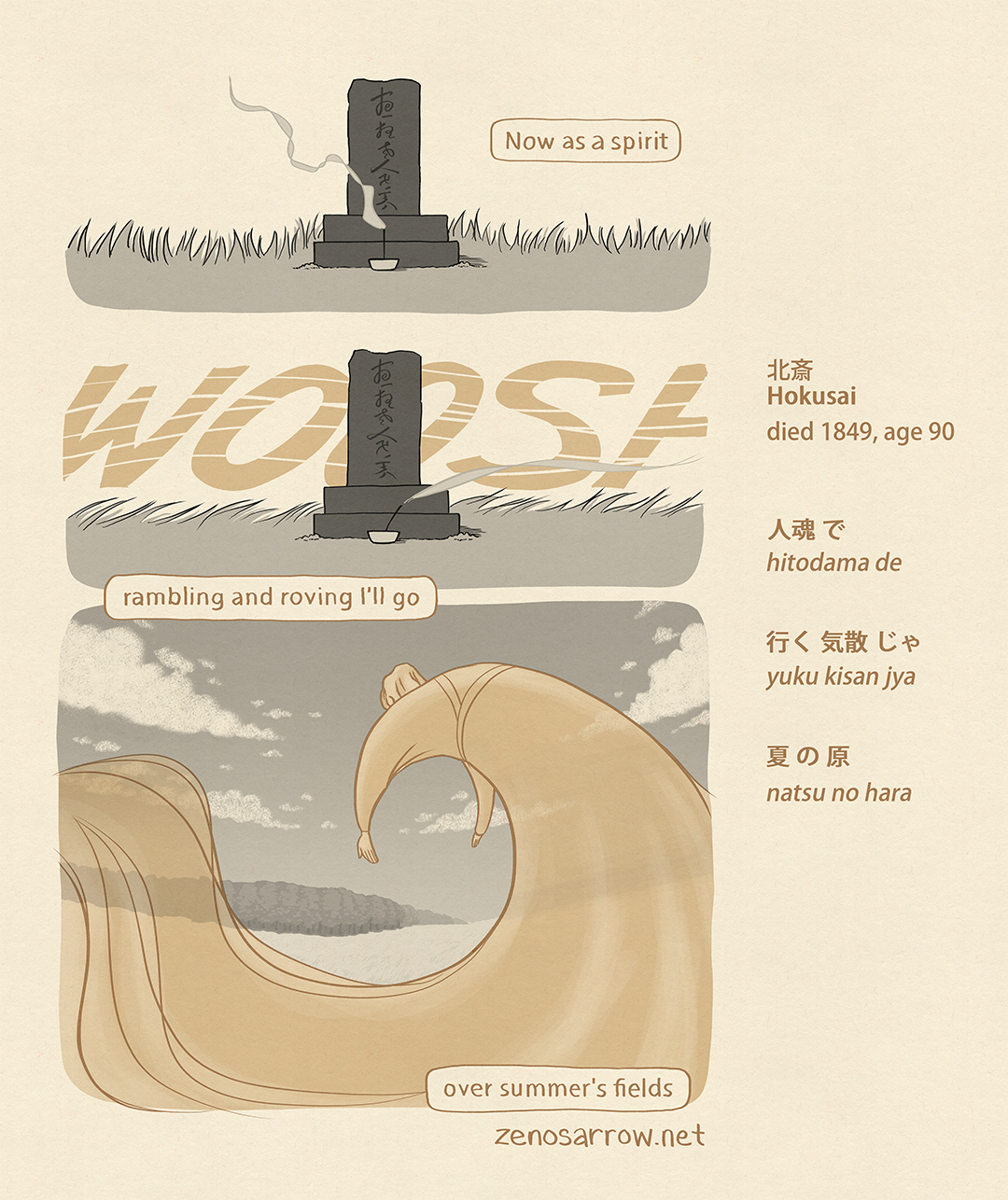

北斎の辞世 Hokusai’s Death Poem

北斎 Hokusai (died 1849, age 90)

人魂 で

hitodama de

行く 気散 じゃ

yuku kisan jya

夏 の 原

natsu no hara

Translation:

Now as a spirit

rambling and roving I’ll go

over summer’s fields

Notes

Speaking of negative space (last week), it is very important in Hokusai’s composition for The Great Wave Off Kanagawa. The sea and the sky take up similar amounts of space in the piece, and mirror each other in their shapes. But as is often observed, the sea in the foreground is active, violent, dangerous, while the sky and mountain in the background are sparse, steady, calm.

If it didn’t jump out to you, the third panel is an homage to Hokusai’s Wave, with a similar, but mirrored, composition.

Does Hokusai’s second line have 7 syllables?

You might have read Hokusai’s second line and been confused that it seems to have fewer than 7 syllables. Well, it turns out that Japanese haiku are actually based on what are called “mora”, the smallest linguistic unit of timing, which can be shorter than a syllable. For example, the ん (“n”) sound that comes at the end of some words in Japanese, like at the end of “kisan”, is counted as another beat in Japanese even though it may sound like one “syllable” in speech. Thus, “kisan” would actually count as 3 morae rather than 2 syllables: ki-sa-n.

This is going to get super weedsy wrestling with the ambiguities in Hoffmann’s text, so read on only if you dare!

That gets us to 6 syllables/morae? Here we have another point of my frustration with Hoffmann’s using only romaji. I believe 気散じ (“kisanji” meaning recreation, diversion, relaxation) makes the most sense among potential translations for Hoffmann’s romaji “kisan ja”. It could be that there was a contraction of “ji” and “ya” (a sentence ending copula), getting us to “ja” / “jya”.

Or maybe in Hokusai’s time the phrase was used differently, just as “kisan”, meaning the “ja” at the end is “ja” in its function as a copula. I found one other instance of “ja” in Hoffmann’s compilation, and there, too, it seemed to stand for 2 morae. Though in that other poem, if Hoffmann’s romaji is accurate (“gatten ja”), then the “ja” could only count for one, since he has a pause in the “gatten” with the double “t”. However, it appears that in most cases “gatten” is actually pronounced “gaten”, just 3 morae and not the 4 morae that “gatten” takes up. There’s only one use case of “gatten” with the “tt” pronunciation, and that’s as part of a larger phrase that isn’t used in the aforementioned poem. Which makes me think Hoffmann’s romaji is in error, and early modern Japanese considered “ja”/ “jya” to be 2 morae.2

“We are a wave appearing on the surface of the ocean. The body of a wave does not last very long – perhaps only ten to twenty seconds. The wave is subject to beginning and ending, to going up and coming down. The wave may be caught in the idea that ‘I am here now and I won’t be here later.’ And the wave may feel afraid or even angry. But the wave also has her ocean body. She has come from the ocean, and she will go back to the ocean. She has both her wave body and her ocean body. She is not only a wave; she is also the ocean. The wave does not need to look for a separate ocean body, because she is in this very moment both her wave body and her ocean body. As soon as the wave can go back to herself and touch her true nature, which is water, then all fear and anxiety disappear. ~ Thich Nhat Hanh.”

I prefer “jya” with the “y” because it reflects that the kana じゃis composed of a “ji” and a small “ya”. There are other sounds where the “y” makes a difference. For example, か“ka” lacks a “y” sound whereas きゃ“kya” has a “y” sound when read aloud. きゃ, like じゃ, is “ki” and a small “ya”. So to me, writing じゃas “jya” with a “y” keeps things consistent.

I got a good chill looking at your visualization, still and fast. Matching the color of the sound effect with the spirit was a fantastic touch.