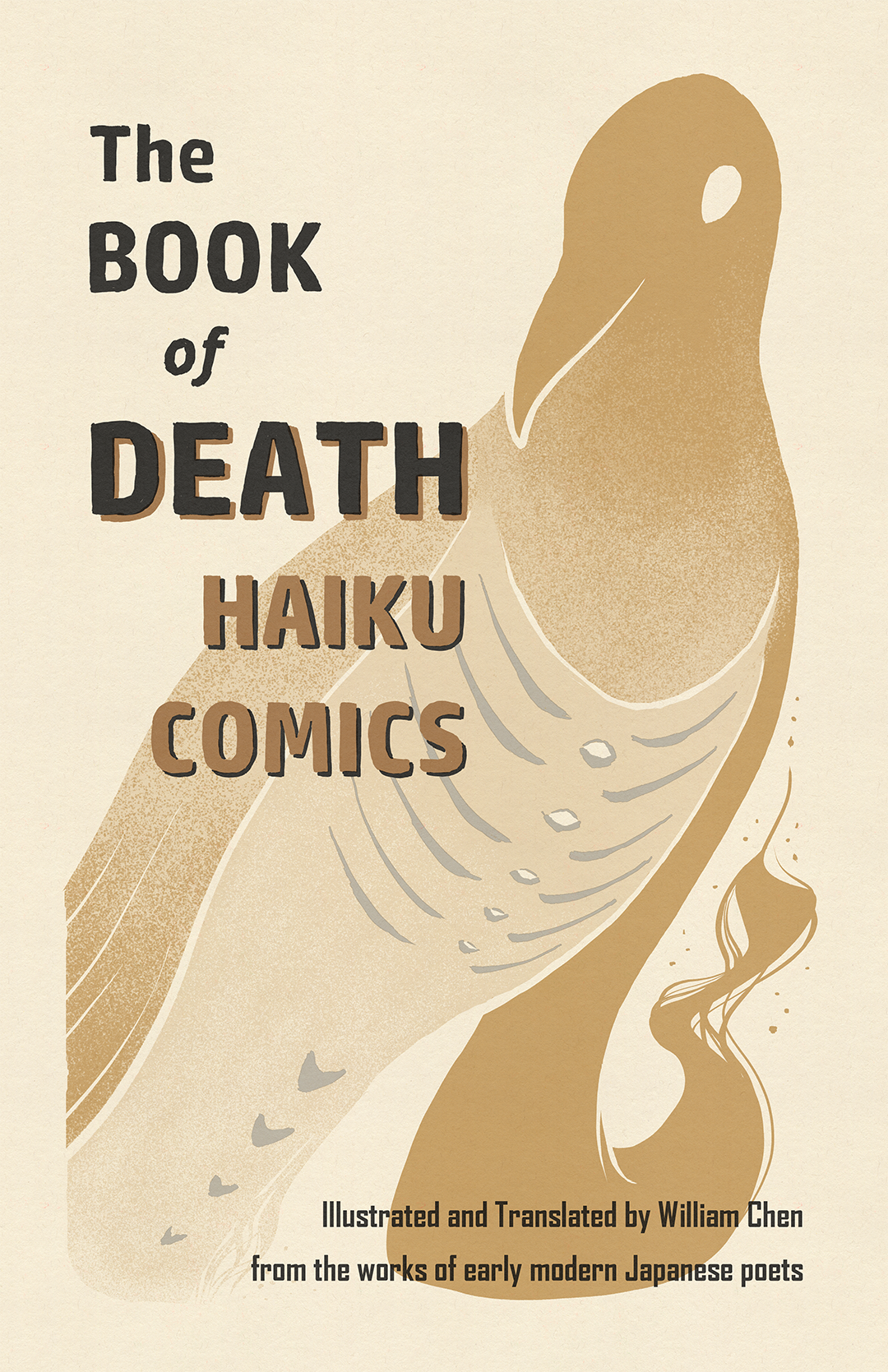

The BOOK of DEATH Haiku Comics

Poetry comics illustrated and translated from the works of early modern Japanese poets

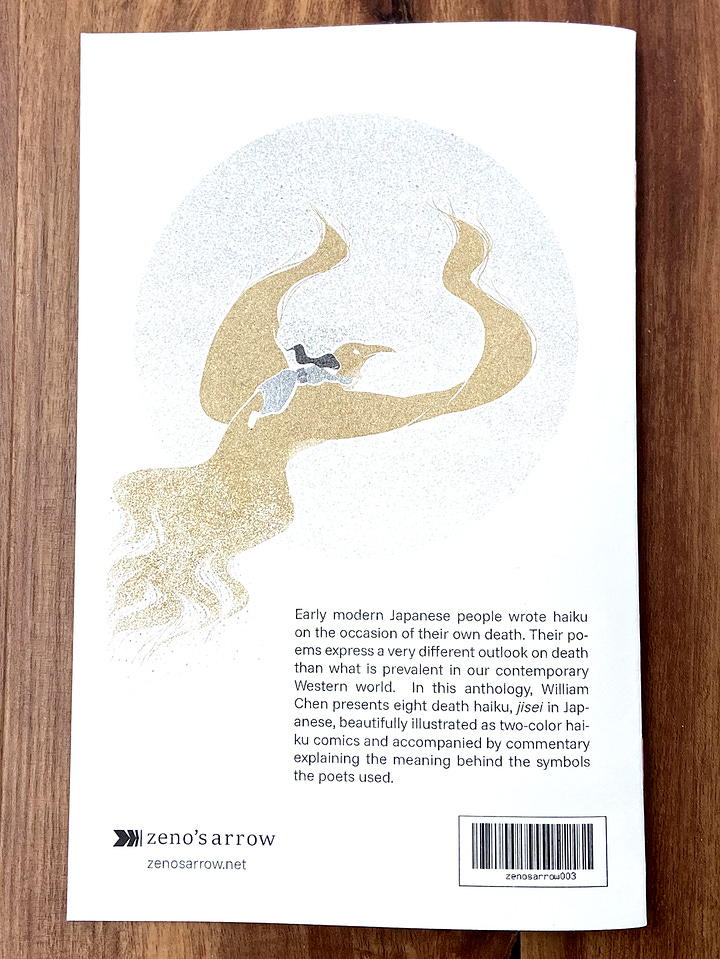

Early modern Japanese people wrote haiku on the occasion of their own death. Their poems express a very different outlook on death than what is prevalent in our contemporary Western world. In this anthology, William Chen presents eight death haiku, jisei in Japanese, beautifully illustrated as two-color haiku comics and accompanied by commentary explaining the meaning behind the symbols the poets used.

Where to Find The BOOK of DEATH Haiku Comics

Buy Direct

You can order a physical copy of The BOOK of DEATH Haiku Comics directly from my shop. As an author, direct sales are the most helpful.

Read Online

辞世 jisei, which come from Japan, are poems written on the occasion of one’s own death. I don’t remember how I stumbled on them, but when I did, death haiku immediately struck me as a fascinating subject for interpreting and illustrating as poetry comics.

You can read the haiku comics at the following links:

About This Series

Yoel Hoffmann, who was a professor of Japanese poetry, Buddhism, and philosophy at the University of Haifa, wrote a book titled Japanese Death Poems. In it, he dives deep into the background and history of Japanese poetry, particularly haiku, historical beliefs about death in Japanese culture, and death poetry as a practice. The bulk of the book is a curated survey of hundreds of death haiku written by Zen monks and haiku poets over the pre-modern centuries.

Acknowledgement

This death haiku comics project of mine owes much to Hoffmann’s book, without which I wouldn’t have any of the poetry with which to work, nor many tidbits of context and meaning to help with my own interpretation of the poems. Heck, I wouldn’t have even known about jisei since there’s not much writing about it in English beyond Hoffmann’s book.

Death in Japanese Culture

It may be helpful to say a little about death in Japanese culture to help you understand some context for how these poems don’t come from a place of fear and abhorrence the way we might expect coming from a Western culture. I am by no means an expert, but fortunately Hoffman offers a lot of history in his book before diving into the death haiku.

Hoffmann notes that:

“Many Japanese prepare for death as soon as they feel their time is near. A will is written to settle the distribution of property and keepsakes among relatives and friends. For the most part, these arrangements take place in an atmosphere of serenity, with almost pleasurable expectation of the voyage to the next world. These preparations do not merely reflect a realistic attitude toward circumstances; they also inspire calmness in the dying allowing them to settle spiritual accounts and to ask pardon for past misdeeds.”1

And although writing death poems as a salutation to life is no longer so widespread as it once was, Hoffmann says that “principally those who have cared for poetry” still do today.

It’s interesting to think about why Japan may have had and still have a much more accepting view of death as a part of life than Western cultures do. Hoffmann observes that Japan’s historical religions, and still primary ones today, first Shintoism and then Buddhism, don’t have a god judging you after death like the Abrahamic religions do.2 Furthermore, in the West death is an individual affair while in Japan death, like life, is a group (usually the family) affair, with the deceased believed to still remain connected to the daily lives of the living. Hoffmann speculates that these customs may make death less scary to Japanese people.

A Note About My Approach To Translating the Haiku

You may already be familiar with the format of Japanese haiku, as it’s had some penetration into American culture.3 They’re very short poems, with just three lines and proscribed syllable counts of 5-7-5. You have to be especially efficient with your words when writing haiku.

Translating haiku then presents an additional challenge: you’re not only making decisions around how best to convey the meaning of the original Japanese poem, but also balancing whether to stick with the 5-7-5 syllable structure.

Hoffmann didn’t bother much with the haiku syllable structure, opting to focus on translating the meaning. He notes that when translations have focused meticulously on the syllable structure, it’s often at the expense of accuracy of the translation.4 Hoffmann presents his translation alongside the romaji (romanization of Japanese language) of the original poem so you can see the syllables following the haiku form. This approach makes sense to me: communicating the meaning is what matters—getting the feeling, the atmosphere, the idea, the emotion across the chasm to the foreign language reader. And then you can combine it with seeing the original language sounds and cadence of the haiku to convey the formal aspects of the poetry.

But I noticed that Hoffmann’s translations sometimes deviate somewhat from the meaning of the original Japanese, too. Sometimes an element of the poem would be missing in his translation, or his translation expressed a different feeling than the original, to me. If one is constrained by syllables, I could see that forcing one to change the meaning of the poem to fit into the narrow mold. But with the freedom from the syllable constraint, it seems to me that it should be easier to more faithfully reflect the original.

On the other hand, there’s something to be said for the beauty of how the words read in the translation versus being a strict transliteration, too. As Hoffmann says, “While free style [not adhering to the structure] lessens the number of formal constraints on the translator, it demands greater attention to the choice and arrangement of words.” But my reaction was that his choices could go too far in changing the precise, crystallized moment being expressed with the very few syllables of the haiku.

Another thing that I missed in Hoffmann’s presentation of the poems is that he only presents the romaji of the original poems, and leaves out the kanji/hiragana. For non-Japanese speakers, this might not be much of a loss. But for me, they would have been helpful to understand the original poet’s intentions, and see the choices Hoffmann made in his translations.

The upshot of all this is that I found myself wanting to do my own translations of the poems to go with my illustrations of the poems. So to pursue this project, I am both back translating the romaji into kanji/hiragana and retranslating the poem into English, as well as illustrating the poem as a comic.

Cultural Barriers to Translating Haiku

There are so few syllables to work with in haiku that the poems rely heavily on commonly understood (to their contemporaries in Japan) symbols to deliver their meaning. This means that simply translating the words into English or even images will still miss a lot without also explaining the symbolism.

Although, in images’ favor, they can get at the goal of translation much more directly than translating into another verbal language. This is because imagery goes directly to (some of) the sensations and ideas that words point at, whereas translating from one verbal language to another means you’re trying to crosswalk from one system of abstraction to another system of abstraction, both of which are pointing at a third thing.

In any case, because of the importance of symbolism, I’m also including some short notes about the symbols to help my comics speak to the reader. But I want this series to be primarily a comics illustration project, rather than a research and writing project about Japanese history and culture.

For more about Japanese death poetry, I recommend Hoffmann’s book. He does a great job surveying their development over Japanese history and providing background on the symbols used.

This ad-free and plain ol’ free publication runs on the positive vibes coming from readers like you. Subscribe to send me more positive vibes.

Interested in reading other comics by me? Check them out at the links below:

Yoel Hoffmann. Japanese Death Poems. (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2018), 29-30.

Ibid., 32.

I’m actually not italicizing the word because there seems to be a decent level of familiarity with them.

Hoffmann, 23.