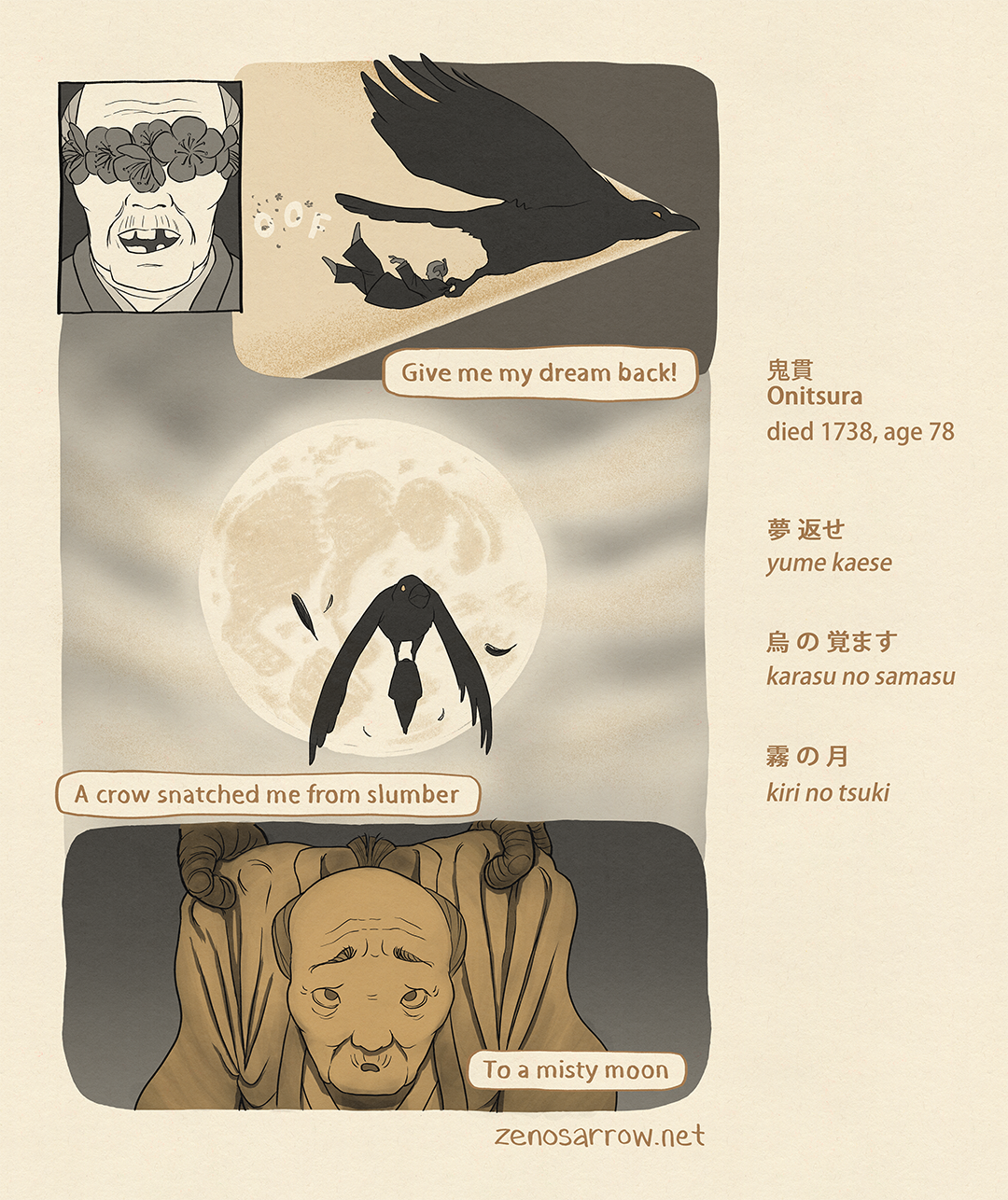

Onitsura's Rude Raven

An early modern Japanese death poem by Onitsura, translated and illustrated as a poetry comic

I bring you death haiku comic number 2. These are fun to come up with the visuals for, woo!

My comic for Onitsura’s death haiku comes right after the break, but first:

A Note about Death in Japanese Culture

I thought it would be helpful to say a little about death in Japanese culture to help you understand some context for how these poems don’t come from a place of fear and abhorrence the way we might expect coming from a Western culture. I am by no means an expert, but fortunately Yoel Hoffman offers a lot of history in his book before diving into the death haiku.

Hoffmann notes that:

“Many Japanese prepare for death as soon as they feel their time is near. A will is written to settle the distribution of property and keepsakes among relatives and friends. For the most part, these arrangements take place in an atmosphere of serenity, with almost pleasurable expectation of the voyage to the next world. These preparations do not merely reflect a realistic attitude toward circumstances; they also inspire calmness in the dying allowing them to settle spiritual accounts and to ask pardon for past misdeeds.”1

And although writing death poems as a salutation to life is no longer so widespread as it once was, Hoffmann says that “principally those who have cared for poetry” still do today.

It’s interesting to think about why Japan may have had and still have a much more accepting view of death as a part of life than Western cultures do. Hoffmann observes that Japan’s historical religions, and still primary ones today, first Shintoism and then Buddhism, don’t have a god judging you after death like the Abrahamic religions do.2 Furthermore, in the West death is an individual affair while in Japan death, like life, is a group (usually the family) affair, with the deceased believed to still remain connected to the daily lives of the living. Hoffmann speculates that these customs may make death less scary to Japanese people.

This ad-free and plain ol’ free publication runs on the positive vibes coming from readers like you. Subscribe to send me more positive vibes.

鬼貫の辞世 Onitsura’s Death Poem

鬼貫 Onitsura (died 1738, age 78)

夢 返せ

yume kaese

烏 の 覚ます

karasu no samasu

霧 の 月

kiri no tsuki

Translation:

Give me my dream back!

A crow snatched me from slumber

To a misty moon

Notes

On life being a dream:

Buddhism came to Japan via China in the seventh century, and over the following centuries came to have more and more influence on Japanese culture. This included the view that life is an illusion or dream.3

On crows:

Hoffmann notes that “the ancient Japanese believed that the dead turned into birds, or perhaps that birds carried the dead to another world. To this day it is thought that ravens embody the souls of the dead [...]”4

On the moon:

The moon could represent several things: on a simple level, Hoffman notes that the moon was considered an autumnal image by default unless the context indicated otherwise.5Seasonal imagery has been a key convention of haikus since the 16th century in Japan.6

More significant to death poetry, though, Hoffmann also observes that in a death poem by Oriku, who commit suicide to escape her cruel mother-in-law, the moon represents salvation in the world beyond our mortal realm.7 And in another interpretation that could be relevant to Onitsura’s poem, the full moon can symbolize enlightenment, with its circular shape echoing the ink circle paintings of enlightenment (ensou) in Japanese Buddhism.8

On the rabbit in the moon:

This isn’t in Onitsura’s haiku at all, but I put a rabbit on the moon because in Japanese folklore it’s a rabbit on the moon and not a “man in the moon”.

On flowers:

Onitsura’s poem doesn’t mention flowers, but I wanted to use another visual device to illustrate his use of the dream metaphor for life. It occurred to me to hark back to the flowers in Gozan’s poem last week, which evoked the ephemerality of life. These also were handy in that they could help me make the crow’s rude awakening more impactful.

A hat tip to Keezy Young, local Seattle graphic novelist, whose Eisner nominated short comic, Sunflowers (it’s good!), inspired in me the idea to use flowers to symbolize being under an illusion. In her comic, Young uses sunflowers covering her eyes to indicate being in a state of hypomania.

Yoel Hoffmann. Japanese Death Poems. (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2018), 29-30.

Ibid., 32.

Ibid., 36-37.

Ibid., 34.

Ibid., 26.

Ibid., 22.

Ibid., 65.

Ibid., 288.