Gozan's Serendipitous Sermon

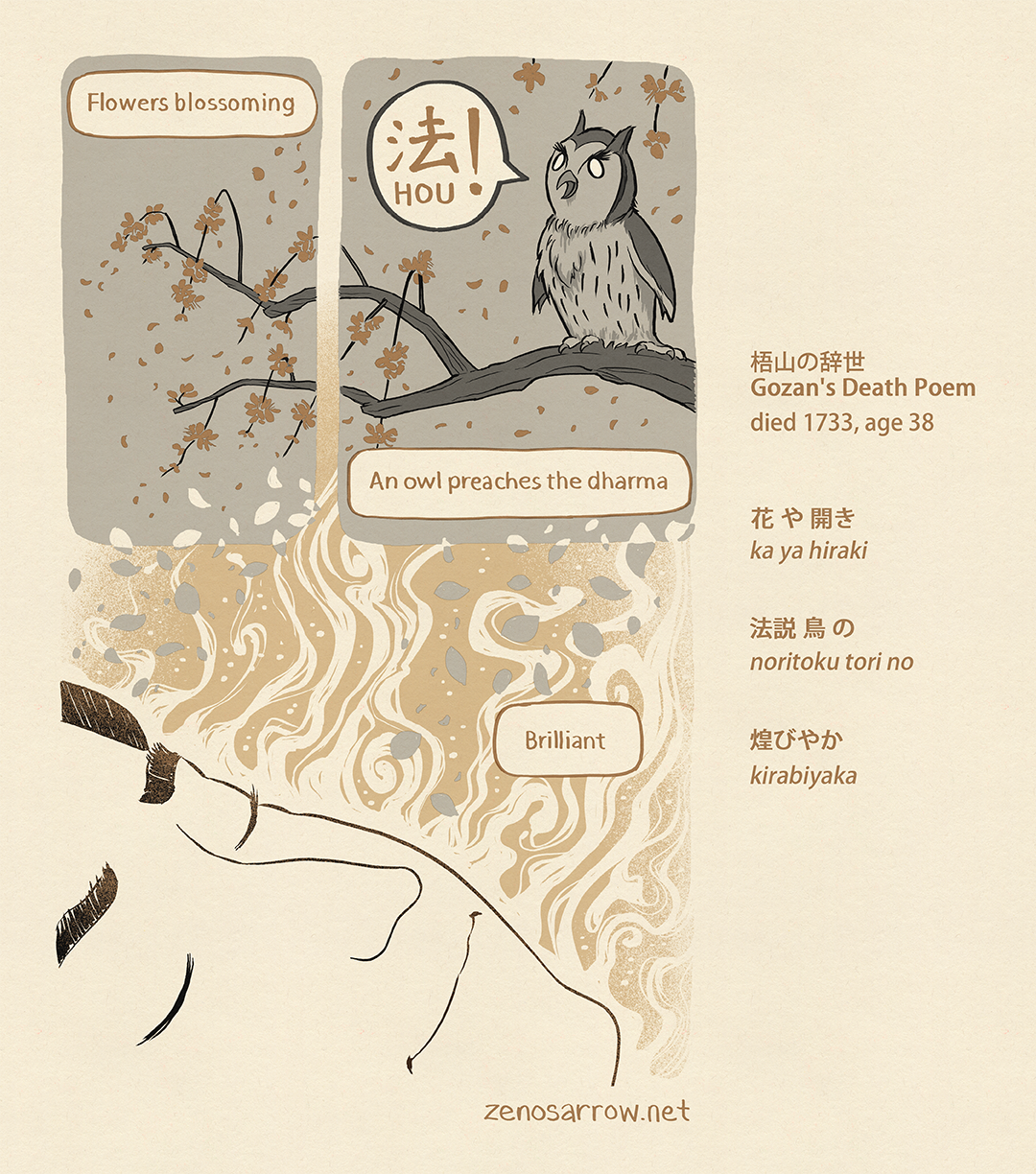

An early modern Japanese death poem by Gozan, translated and illustrated as a poetry comic

Today, I’m psyched to kick off my new comic project: death haiku comics. Here we go!

With this first post, I’ll start by sharing my comic and some notes about what’s going on with it. Then I’ll get into a little background on how this project came to be and my approach to translating the haikus.

Future death haiku comic posts will follow the format of comic + notes. I’ve set up a home page for the death haiku comics, too, where you’ll be able to find links to all the comics when they’re published. Swing by the page for the gorgeous cover art! I feel really good about it. But didn’t share it in this post since this one’s for Gozan’s death haiku comic and it seemed like it’d be cumbersome to have it in this post which is already sharing a lot of the background discussion about this death haiku comics series.

Here are the section links for today’s post:

I am very curious to hear your thoughts as I launch this series, so please don’t hesitate to share with me. Hope you enjoy reading these as much as I do creating them.

Till next time-

William

This ad-free and plain ol’ free publication runs on the positive vibes coming from readers like you. Subscribe to send me more positive vibes.

梧山の辞世 Gozan’s Death Poem

梧山 Gozan (died in 1733, age 38)

花 や 開き

ka ya hiraki

法説く 鳥 の

noritoku tori no

煌びやか

kirabiyaka

Translation:

Flowers blossoming

An owl preaches the dharma

Brilliant

Notes

Notice that Gozan’s death haiku is a palindrome! Yoel Hoffmann notes in Japanese Death Poems that this type of poem is called a kaibun poem, and was popular in the 18th and 19th centuries.1

But, you protest, there is a “hi” in the first line that is being matched up with a “bi” in the last line! Maybe so, but there is a sort of parity between ひ“hi”, び“bi”, and ぴ“pi” in Japanese, with “bi” and “pi” having the same base hiragana as “hi”, plus a modifier.

Also, we’ll notice that haiku writers sometimes take advantage of fudge factors to get their poems to fit the 5-7-5 syllable format, like phrases that while not ungrammatical don’t add a ton to the meaning of the poem. The の“no”that wraps up the second line in Gozan’s poem is an example of this. In related vein, Gozan uses the Chinese-derived onyomi pronunciation of the character 花, ka, meaning flower, instead of the typical Japanese kunyomi pronunciation, hana.

I could have added some words to get the last line to five syllables (e.g. “Oh, how brilliant”), but it’s already a translation, the original lacks such an exclamation, and I think the simple statement of “brilliant” suits the tone better.

On the illusory nature of life:

Buddhism came to Japan via China in the seventh century, and over the following centuries came to have more and more influence on Japanese culture. This included the view that life is an illusion or dream.2

On flowers:

During the Heian period (794-1185) of Japanese history, flowers became the principle symbol representing the ephemerality of life.3

On owls:

The Japanese onomatopoeia for the sound an owl makes, “hou”, is a pun with the Chinese-derived reading (onyomi) of the kanji 法, meaning “law”, or more relevant to this case, “dharma” or “Buddha’s law”. Gozan uses the Japanese reading (kunyomi) of the character, “nori”, in his poem.4

So What’s Going On Here?

辞世 jisei, which come from Japan, are poems written on the occasion of one’s own death. I don’t remember how I stumbled on them, but when I did, death haiku immediately struck me as a fascinating subject for interpreting and illustrating as poetry comics.

Yoel Hoffmann, who was a professor of Japanese poetry, Buddhism, and philosophy at the University of Haifa, wrote a book titled Japanese Death Poems. In it, he dives deep into the background and history of Japanese poetry, particularly haiku, historical beliefs about death in Japanese culture, and death poetry as a practice. The bulk of the book is a curated survey of hundreds of death haiku written by Zen monks and haiku poets over the pre-modern centuries.

Acknowledgement

This death haiku comics project of mine owes much to Hoffmann’s book, without which I wouldn’t have any of the poetry with which to work, nor many tidbits of context and meaning to help with my own interpretation of the poems. Heck, I wouldn’t have even known about jisei since there’s not much writing about it in English beyond Hoffmann’s book.

A Note About My Approach To Translating the Haiku

You may already be familiar with the format of Japanese haiku, as it’s had some penetration into American culture.5 They’re very short poems, with just three lines and proscribed syllable counts of 5-7-5. You have to be especially efficient with your words when writing haiku.

Translating haiku then presents an additional challenge: you’re not only making decisions around how best to convey the meaning of the original Japanese poem, but also balancing whether to stick with the 5-7-5 syllable structure.

Hoffmann didn’t bother much with the haiku syllable structure, opting to focus on translating the meaning. He notes that when translations have focused meticulously on the syllable structure, it’s often at the expense of accuracy of the translation.6 Hoffmann presents his translation alongside the romaji (romanization of Japanese language) of the original poem so you can see the syllables following the haiku form. This approach makes sense to me: communicating the meaning is what matters—getting the feeling, the atmosphere, the idea, the emotion across the chasm to the foreign language reader. And then you can combine it with seeing the original language sounds and cadence of the haiku to convey the formal aspects of the poetry.

But I noticed that Hoffmann’s translations sometimes deviate somewhat from the meaning of the original Japanese, too. Sometimes an element of the poem would be missing in his translation, or his translation expressed a different feeling than the original, to me. If one is constrained by syllables, I could see that forcing one to change the meaning of the poem to fit into the narrow mold. But with the freedom from the syllable constraint, it seems to me that it should be easier to more faithfully reflect the original.

On the other hand, there’s something to be said for the beauty of how the words read in the translation versus being a strict transliteration, too. As Hoffmann says, “While free style [not adhering to the structure] lessens the number of formal constraints on the translator, it demands greater attention to the choice and arrangement of words.” But my reaction was that his choices could go too far in changing the precise, crystallized moment being expressed with the very few syllables of the haiku.

Another thing that I missed in Hoffmann’s presentation of the poems is that he only presents the romaji of the original poems, and leaves out the kanji/hiragana. For non-Japanese speakers, this might not be much of a loss. But for me, they would have been helpful to understand the original poet’s intentions, and see the choices Hoffmann made in his translations.

The upshot of all this is that I found myself wanting to do my own translations of the poems to go with my illustrations of the poems. So to pursue this project, I am both back translating the romaji into kanji/hiragana and retranslating the poem into English, as well as illustrating the poem as a comic.

Cultural Barriers to Translating Haiku

There are so few syllables to work with in haiku that the poems rely heavily on commonly understood (to their contemporaries in Japan) symbols to deliver their meaning. This means that simply translating the words into English or even images will still miss a lot without also explaining the symbolism.

Although, in images’ favor, they can get at the goal of translation much more directly than translating into another verbal language. This is because imagery goes directly to (some of) the sensations and ideas that words point at, whereas translating from one verbal language to another means you’re trying to crosswalk from one system of abstraction to another system of abstraction, both of which are pointing at a third thing.

In any case, because of the importance of symbolism, I’m also including some short notes about the symbols to help my comics speak to the reader. But I want this series to be primarily a comics illustration project, rather than a research and writing project about Japanese history and culture.

For more about Japanese death poetry, I recommend Hoffmann’s book. He does a great job surveying their development over Japanese history and providing background on the symbols used.

Yoel Hoffmann. Japanese Death Poems. (Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2018), 175.

Ibid., 36-37.

Ibid., 46.

Ibid., 175-176.

I’m actually not italicizing the word because there seems to be a decent level of familiarity with them.

Hoffmann, p.23.

The 法 is very clever!

Fascinating new series, was not expecting poetry comics from you but the more the merrier 😎

William, well done!! Soooo interesting!